Journal of Geographical Sciences >

Intercity connections and a world city network based on international sport events: Empirical studies on the Beijing, London, and Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games

|

Xue Desheng (1969-), PhD and Professor, E-mail: eesxds@mail.sysu.edu.cn |

Received date: 2021-03-25

Accepted date: 2021-08-14

Online published: 2022-02-25

Supported by

National Natural Science Foundation of China(41930646)

Copyright

With so many sports becoming increasingly popular, sports have come to play an important role in promoting the process of globalization and formatting the world city network (WCN). Previous studies have constructed the WCN based on the distribution of international sport federations (ISFs) and the sites of international sport events (ISEs), but there is still a lack of systematic research on the intercity connections caused by ISEs. Taking three most recent Olympic Games as cases, this paper explores intercity connections and WCN based on ISEs. The results show that (1) the Olympic WCN has city nodes around the world except in Antarctica, and the number and activity values of the cities in host countries may increase intensively during the Olympic Games. (2) A hierarchical city system with four tiers (global central cities, specialized central cities, national central cities and specialized cities) is formed by the intercity connections caused by the Olympic Games. (3) The WCN based on the Olympic Games, is made up of many subnetworks, while many differences occur due to the diverse decisions made by the Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games (OCOG), host cities or even host countries in the events associated with sponsorship activity and publicity activity. This study not only broadens the relevant fields of sports culture-oriented WCN research but also explores the instability of the WCN, which makes it an effective reference for WCN research based on ISEs.

Key words: globalization; world city network; Olympic Games; hierarchy

XUE Desheng , OU Yubin . Intercity connections and a world city network based on international sport events: Empirical studies on the Beijing, London, and Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games[J]. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 2021 , 31(12) : 1791 -1815 . DOI: 10.1007/s11442-021-1923-z

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of the connections caused by different events |

Table 1 Activity values of the subjects of the specific events |

| Competition for the right to host the Olympic Games | Competition for athletes’ qualification to participate in the Olympic Games | TOP programme | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Activity values | Subjects | Activity values | Subjects | Activity values | |

| IOC | 5 | IOC | 5 | IOC | 5 | |

| Competition committee of host cities | 4 | OCOG | 4 | OCOG | 4 | |

| Competition committee of cities that participate in the second round | 2 | ISFs | 4 | MNCs | 4 | |

| Competition committee of cities that participate in the first round | 1 | Regional headquarters of the Olympic committee | 3 | |||

| NOCs | 2 | |||||

| NSFs | 1 | |||||

| OCOG sponsorship programme | Torch relay | TV broadcast | ||||

| Subjects | Activity values | Subjects | Activity values | Subjects | Activity values | |

| OCOG | 5 | OCOG | 5 | OCOG | 5 | |

| OCOG partners | 3 | IOC | 4 | IOC | 4 | |

| OCOG sponsors | 2 | Government of Athens | 3 | Rights-holding broadcasters | 3 | |

| OCOG providers | 1 | Government of foreign cities | 2 | Non-rights-holding broadcasters | 1 | |

| Government of domestic cities | 1 | |||||

Figure 2 Regional distributions of activity values based on three Olympic Games |

Table 2 Number of city nodes in different regions |

| Beijing Olympic Games | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | Chinese mainland | Asia except China | Europe | America except LA | Latin America | Africa | Oceania | Sum |

| Count of nations/regions | 1 | 44 | 53 | 2 | 47 | 54 | 24 | 225 |

| Count of cities | 108 | 60 | 114 | 22 | 60 | 69 | 31 | 464 |

| London Olympic Games | ||||||||

| Regions | Britain | Asia | Europe except Britain | America except LA | Latin America | Africa | Oceania | Sum |

| Count of nations/regions | 1 | 45 | 52 | 2 | 47 | 54 | 24 | 225 |

| Count of cities | 65 | 59 | 140 | 19 | 59 | 69 | 32 | 443 |

| Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games | ||||||||

| Regions | Brazil | Asia | Europe | America except LA | LA except Brazil | Africa | Oceania | Sum |

| Count of nations/regions | 1 | 45 | 53 | 2 | 46 | 54 | 24 | 225 |

| Count of cities | 324 | 58 | 138 | 19 | 56 | 70 | 32 | 697 |

Note: As Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan have independent Olympic committees and sports federations, these three regions are relatively independent in the process of organizing and hosting the Olympic Games, so they are included in the statistical data of other cities and regions in Asia. |

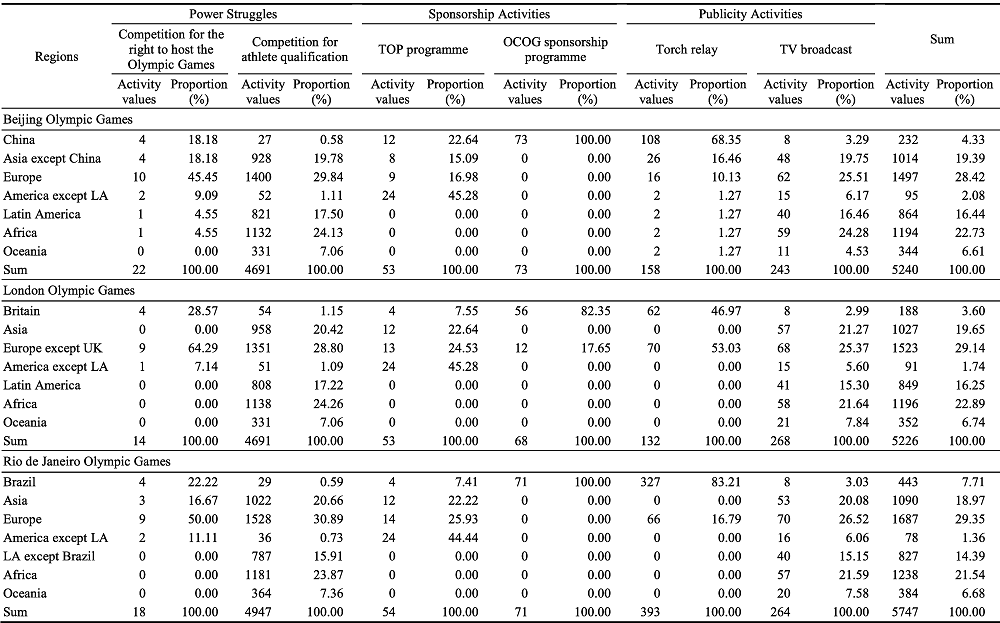

Table 3 Regional distribution and their contribution to total activity values in different events of different Olympic Games |

|

Table 4 Number of city nodes in different countries of the three Olympic Games |

| Count of city nodes in certain countries | Count of countries | Countries/Regions |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing Olympic Games | ||

| Over 100 | 1 | China (108) |

| 10-100 | 4 | America (14), Britain (12), Germany (12), Switzerland (11) |

| 5-9 | 4 | Canada (8), Australia (6), Austria (6), Netherlands (5) |

| 3-4 | 8 | Belgium (4), Guam (4), Bolivia (3), Columbia (3), Pakistan (3), South Africa (3), Bosnia and Herzegovina (3), New Zealand (3) |

| 2 | 48 | Myanmar, Morocco, etc. |

| 1 | 160 | Algeria, Albania, etc. |

| London Olympic Games | ||

| Over 100 | 1 | Britain (65) |

| 10-100 | 4 | Greece (34), America (13), Germany (13), Switzerland (11) |

| 5-9 | 4 | Canada (6), Australia (5), Austria (6), Netherlands (5) |

| 3-4 | 9 | Belgium (4); Guam (4); France (3), Bolivia (3), Columbia (3), Pakistan (3), Bosnia and Herzegovina (3), New Zealand (3), South Africa (3) |

| 2 | 49 | Myanmar, Morocco, etc. |

| 1 | 158 | Algeria, Albania, etc. |

| Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games | ||

| Over 100 | 1 | Brazil (324) |

| 10-100 | 5 | Greece (28), America (13), Britain (12), Germany (12), Switzerland (10) |

| 5-9 | 4 | Canada (6), Australia (5), Austria (6), Netherlands (5) |

| 3-4 | 8 | Belgium (4), Guam (4), Pakistan (3), Bolivia (3), Columbia (3), South Africa (3), Bosnia and Herzegovina (3), New Zealand (3) |

| 2 | 43 | Myanmar, Morocco, etc. |

| 1 | 164 | Algeria, Albania, etc. |

Table 5 Different levels of urban nodes in terms of network connectivity based on different Olympic Games |

| Levels (Connectivity) | Count of cities | Cities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing Olympic Games | |||

| Global central cities (Over 1000) | 2 | Lausanne, Beijing | |

| Specialized central cities (41-1000) | Specialized regional central cities (96-1000) | 12 | Abuja, Rome, Kuwait City, etc. |

| Specialized transnational central cities (41-95) | 27 | Istanbul, Toronto, Osaka, etc. | |

| National central cities (16-40) | 194 | Ankara, Lisbon, Melbourne, etc. | |

| Specialized cities (2-15) | 209 | Guangzhou, Canberra, Birmingham, etc. | |

| London Olympic Games | |||

| Global central cities(Over 1000) | 2 | Lausanne, London | |

| Specialized central cities (41-1000) | Specialized regional central cities (80-1000) | 15 | Mexico City, Abuja, Rome, etc. |

| Specialized transnational central cities (41-79) | 24 | Toronto, Beijing, Miami, etc. | |

| National central cities (16-40) | 192 | Ankara, Sydney, Athens, etc. | |

| Specialized cities (2-15) | 191 | Bridgetown, Sucre, Almaty, etc. | |

| Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games | |||

| Global central cities(Over 1000) | 2 | Lausanne, Rio de Janeiro | |

| Specialized central cities (41-1000) | Specialized regional central cities (86-1000) | 12 | Mexico City, Abuja, Rome, etc. |

| Specialized transnational central cities (41-85) | 24 | Madrid, Toronto, Dublin, etc. | |

| National central cities (16-40) | 196 | Ankara, Sydney, Bridgetown, etc. | |

| Specialized cities (2-15) | 442 | Geneva, Cape Town, Amsterdam, etc. | |

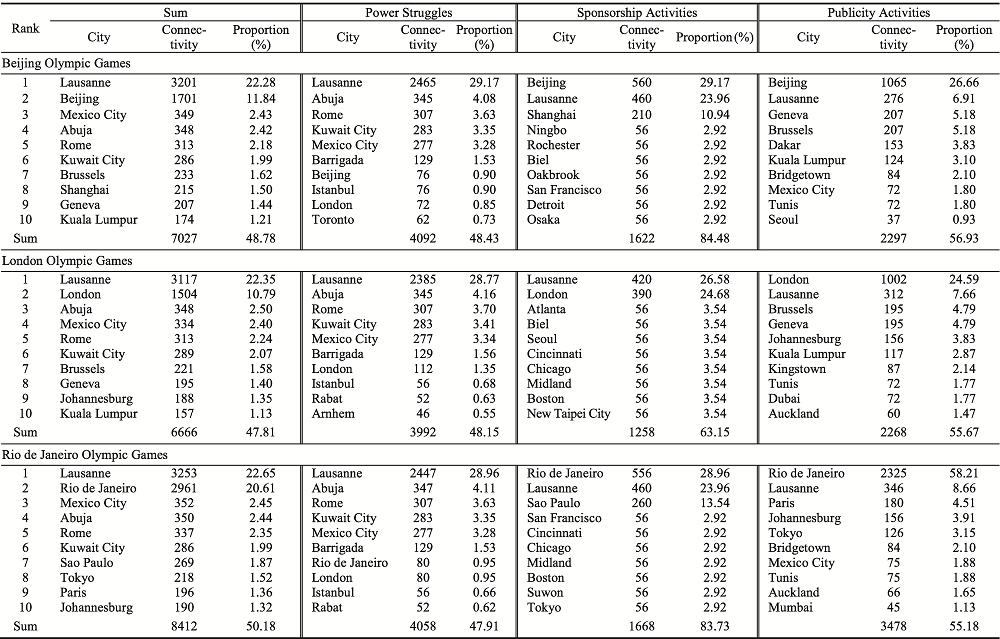

Table 6 Top ten most connected cities for each event in different Olympic Games |

|

Table 7 Betweenness centrality of cities in the world city networks of different Olympic Games |

| Rank | Sum | Power Struggles | Sponsorship Activities | Publicity Activities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Betweenness centrality | City | Betweenness centrality | City | Betweenness centrality | City | Betweenness centrality | |

| Beijing Olympic Games | ||||||||

| 1 | Lausanne | 0.060174 | Lausanne | 0.046732 | Beijing | 0.738095 | Beijing | 0.001244 |

| 2 | Beijing | 0.042567 | Toronto | 0.010258 | Lausanne | 0.476190 | Dakar | 0.000890 |

| 3 | Toronto | 0.008404 | Cairo | 0.004114 | Tunis | 0.000717 | ||

| 4 | Brussels | 0.008139 | Istanbul | 0.003245 | Geneva | 0.000575 | ||

| 5 | Istanbul | 0.006522 | Kuala Lumpur | 0.002948 | Brussels | 0.000575 | ||

| 6 | Cairo | 0.004818 | Havana | 0.000930 | Kuala Lumpur | 0.000545 | ||

| 7 | Paris | 0.004627 | Paris | 0.000913 | Mexico City | 0.000307 | ||

| 8 | Kuala Lumpur | 0.003343 | Beijing | 0.000616 | ||||

| 9 | Tunis | 0.003116 | Bangkok | 0.000616 | ||||

| 10 | Geneva | 0.002337 | Pasig City | 0.000242 | ||||

| Proportion (%) | 94.32 | 99.98 | 100.00 | 100.00 | ||||

| London Olympic Games | ||||||||

| 1 | London | 0.058776 | Lausanne | 0.034593 | London | 0.541667 | London | 0.001021 |

| 2 | Lausanne | 0.045266 | London | 0.021630 | Lausanne | 0.163043 | Johannesburg | 0.000985 |

| 3 | Kuwait City | 0.012117 | Paris | 0.000460 | Kuala Lumpur | 0.000664 | ||

| 4 | Seoul | 0.011938 | Moscow | 0.000460 | Geneva | 0.000615 | ||

| 5 | Brussels | 0.009280 | Madrid | 0.000460 | Brussels | 0.000615 | ||

| 6 | Tunis | 0.007435 | Pasig City | 0.000190 | Kingstown | 0.000429 | ||

| 7 | Johannesburg | 0.007131 | Georgetown | 0.000011 | Auckland | 0.000229 | ||

| 8 | Abuja | 0.005210 | Miami | 0.000183 | ||||

| 9 | Kuala Lumpur | 0.003263 | Tunis | 0.000172 | ||||

| 10 | Geneva | 0.003210 | Dubai | 0.000172 | ||||

| Proportion (%) | 90.26 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 96.73 | ||||

| Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games | ||||||||

| 1 | Rio de Janeiro | 0.032248 | Lausanne | 0.023938 | Lausanne | 0.359477 | Rio de Janeiro | 0.001207 |

| 2 | Lausanne | 0.019943 | Rio de Janeiro | 0.004169 | Rio de Janeiro | 0.333333 | Johannesburg | 0.000297 |

| 3 | Bern | 0.007153 | Tokyo | 0.000919 | Paris | 0.000272 | ||

| 4 | Tunis | 0.006279 | Doha | 0.000919 | Tokyo | 0.000166 | ||

| 5 | Abuja | 0.004968 | Madrid | 0.000605 | Bridgetown | 0.000143 | ||

| 6 | Doha | 0.004473 | Prague | 0.000605 | Auckland | 0.000138 | ||

| 7 | Tokyo | 0.003799 | Baku | 0.000605 | Tunis | 0.000110 | ||

| 8 | Johannesburg | 0.003209 | Abuja | 0.000539 | Mexico City | 0.000110 | ||

| 9 | Kuwait City | 0.002827 | Pasig City | 0.000132 | Mumbai | 0.000041 | ||

| 10 | Paris | 0.000707 | Georgetown | 0.000011 | Rome | 0.000007 | ||

| Proportion (%) | 97.08 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.72 | ||||

Figure 3 Structures of the world city network based on three Olympic Games |

Figure 4 Structures of the world city network based on power struggles in three Olympic Games |

Figure 5 Structures of the world city network based on the sponsorship activities of three Olympic Games |

Figure 6 Structures of the world city network based on the publicity activities of three Olympic Games |

Figure 7 Different kinds of world city networks |

| [1] |

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

|

| [23] |

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

|

| [26] |

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

|

| [31] |

|

| [32] |

|

| [33] |

|

| [34] |

|

| [35] |

|

| [36] |

|

| [37] |

|

| [38] |

|

| [39] |

|

| [40] |

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

|

| [43] |

|

| [44] |

|

| [45] |

|

| [46] |

|

| [47] |

|

| [48] |

|

| [49] |

|

| [50] |

|

| [51] |

|

| [52] |

|

| [53] |

|

| [54] |

|

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |