Journal of Geographical Sciences >

New-type urbanization in China: Predicted trends and investment demand for 2015-2030

Author: Sun Dongqi (1985-), PhD, specialized in economic geography and regional development. E-mail: sundq@igsnrr.ac.cn.

*Corresponding author: Li Yu (1973-), Associate Professor, specialized in urbanization and its eco-environment effects. E-mail: liy@igsnrr.ac.cn

Received date: 2016-07-26

Accepted date: 2016-09-20

Online published: 2017-08-31

Supported by

National Natural Science Foundation of China, No.41501137, No.41530634, No.41271186

Copyright

The future development of new-type urbanization has drawn great attention from both the government and public alike. In this context, the present study had three related research aims. Firstly, it sought to predict the urbanization and population dynamics in China at both national and provincial levels for the period of 2015 to 2030. Secondly, on this basis, it sought to examine the spatial variation of urbanization given the predicted national urbanization rate of 70.12%. Thirdly, it sought to estimate and evaluate the national and provincial demands of investment in the development of new-type urbanization. The main conclusions from this study were as follows: (1) The population size and urbanization rate will reach 1.445 billion and 70.12%, respectively, from 2015 to 2030. (2) The demographic dividend will vanish when the population pressure reaches its maximum. During this period, there will be 70.16 million urban population born. The suburban population that becomes urbanized will be 316.7 million, and thus the net increase in urban population will reach 386 million. (3) Although the urbanization rate of every Chinese province will increase during 2015-2030, it will do so unequally, while differences in urbanization quality among provinces will also be substantial. In some provinces, moreover, the urbanization quality is not compatible with their eco-social development. (4) A total of 4,105,380 billion yuan is required to fund new-type urbanization and the investment demand for each province varies greatly; for example, Guangdong province requires the most funding, amounting to approximately 148 times that required by Tibet, the province in least need of funding. In the final part of this study, policy suggestions concerning the investment of the new-type urbanization are put forward and discussed.

Key words: new-type urbanization; urbanization investment; 2015-2030; forecasting; China

SUN Dongqi , ZHOU Liang , LI Yu , LIU Haimeng , SHEN Xiaoyan , WANG Zedong , WANG Xixi . New-type urbanization in China: Predicted trends and investment demand for 2015-2030[J]. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 2017 , 27(8) : 943 -966 . DOI: 10.1007/s11442-017-1414-4

Table 1 The dynamics of China’s urbanization rate and related factors 2015-2030 |

| Year | Urbani- zation rate (%) | Total population (100 million) | Urban population (100 million) | Rural population (100 million) | Urban population transferred from rural areas (100 million) | GDP (trillion yuan) | GDP/100 million people (trillion yuan) | The structure of the primary, secondary, and tertiary industries (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 48.23 | 13.75 | 6.63 | 7.12 | 0.1836 | 68.2 | 4.96 | 10/45/45 |

| 2016 | 49.77 | 13.81 | 6.87 | 6.94 | 0.1869 | 72.63 | 5.26 | 10/45/45 |

| 2017 | 51.31 | 13.87 | 7.12 | 6.75 | 0.1896 | 77.35 | 5.58 | 10/45/45 |

| 2018 | 52.85 | 13.92 | 7.36 | 6.56 | 0.1911 | 82.38 | 5.92 | 10/44/46 |

| 2019 | 54.38 | 13.97 | 7.6 | 6.37 | 0.1928 | 87.74 | 6.28 | 10/44/46 |

| 2020 | 55.9 | 14.03 | 7.84 | 6.19 | 0.1948 | 93.44 | 6.66 | 10/44/46 |

| 2021 | 57.41 | 14.07 | 8.08 | 5.99 | 0.1966 | 99.51 | 7.07 | 10/44/46 |

| 2022 | 58.91 | 14.12 | 8.32 | 5.8 | 0.1983 | 105.98 | 7.51 | 10/44/46 |

| 2023 | 60.40 | 14.17 | 8.56 | 5.61 | 0.2003 | 112.87 | 7.97 | 10/44/46 |

| 2024 | 61.86 | 14.21 | 8.79 | 5.42 | 0.1997 | 120.21 | 8.46 | 10/44/46 |

| 2025 | 63.30 | 14.26 | 9.03 | 5.23 | 0.1989 | 128.02 | 8.98 | 10/43/47 |

| 2026 | 64.72 | 14.30 | 9.25 | 5.05 | 0.1984 | 136.34 | 9.53 | 10/43/47 |

| 2027 | 66.11 | 14.34 | 9.48 | 4.86 | 0.1965 | 145.2 | 10.13 | 10/43/47 |

| 2028 | 67.48 | 14.38 | 9.7 | 4.68 | 0.1954 | 154.64 | 10.75 | 10/43/47 |

| 2029 | 68.82 | 14.41 | 9.92 | 4.49 | 0.1932 | 164.7 | 11.43 | 10/43/47 |

| 2030 | 70.12 | 14.45 | 10.13 | 4.32 | 0.1903 | 175.4 | 12.14 | 10/43/47 |

Figure 1 Temporal differentiation laws of China’s urbanization rate and the development of the main related factors, 2015-2030 |

Table 2 China’s urbanization rate (by province, %) in 2015, 2020, 2025, and 2030 |

| Provincial regions | 2015 | 2020 | 2025 | 2030 | Provincial regions | 2015 | 2020 | 2025 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 77.13 | 85.02 | 92.32 | 99.46 | Hubei | 46.15 | 53.77 | 61.14 | 67.96 |

| Tianjin | 72.91 | 81.26 | 89.1 | 98.64 | Hunan | 43.58 | 51.82 | 59.85 | 67.36 |

| Hebei | 40.86 | 49.02 | 57.01 | 64.51 | Guangdong | 64.3 | 76.21 | 87.81 | 96.07 |

| Shanxi | 46.95 | 54.74 | 62.3 | 69.27 | Guangxi | 40.86 | 48.49 | 55.95 | 62.9 |

| Inner Mongolia | 52.34 | 60.34 | 68.04 | 75.11 | Hainan | 47.75 | 56.13 | 64.28 | 71.86 |

| Liaoning | 57.67 | 64.3 | 70.51 | 76.04 | Chongqing | 52.09 | 62.77 | 73.24 | 83.09 |

| Jilin | 48.79 | 53.64 | 58.12 | 62.02 | Sichuan | 40.37 | 47.98 | 55.4 | 62.34 |

| Heilongjiang | 50.03 | 54.73 | 59.03 | 62.74 | Guizhou | 32.51 | 38.49 | 44.32 | 49.76 |

| Shanghai | 79.78 | 87.43 | 94.46 | 99.89 | Yunnan | 35.26 | 41.99 | 48.57 | 54.72 |

| Jiangsu | 58.72 | 69.61 | 80.22 | 90.13 | Tibet | 22.38 | 25.77 | 29.03 | 32.02 |

| Zhejiang | 58.69 | 71.41 | 83.92 | 95.73 | Shaanxi | 43.86 | 51.84 | 59.6 | 66.83 |

| Anhui | 42.48 | 50.59 | 58.5 | 65.9 | Gansu | 32.36 | 37.94 | 43.35 | 48.38 |

| Fujian | 56.32 | 67.73 | 78.89 | 89.39 | Qinghai | 40.49 | 45.97 | 51.19 | 55.92 |

| Jiangxi | 42.59 | 50.18 | 57.57 | 64.43 | Ningxia | 43.67 | 50.56 | 57.21 | 63.34 |

| Shandong | 49.56 | 58.28 | 66.77 | 74.66 | Xinjiang | 36.08 | 39.07 | 41.76 | 44.02 |

| Henan | 38.62 | 45.81 | 52.81 | 59.36 | China | 48.23 | 55.9 | 63.3 | 70.12 |

Figure 2 The spatial distribution of China’s projected urbanization rate (by province) for 2015-2030 |

Figure 3 The evaluation system of China’s new-type urbanization quality |

Table 3 The index of national and provincial urbanization quality in 2030 |

| Provincial regions | σ | Provincial regions | σ | Provincial regions | σ | Provincial regions | σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 0.6746 | Shanghai | 0.6788 | Hubei | 0.4377 | Yunnan | 0.1465 |

| Tianjin | 0.6763 | Jiangsu | 0.6273 | Hunan | 0.4452 | Tibet | 0.0067 |

| Hebei | 0.4315 | Zhejiang | 0.6165 | Guangdong | 0.6077 | Shaanxi | 0.2242 |

| Shanxi | 0.2279 | Anhui | 0.3815 | Guangxi | 0.2158 | Gansu | 0.0796 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.4525 | Fujian | 0.5713 | Hainan | 0.3856 | Qinghai | 0.0719 |

| Liaoning | 0.4769 | Jiangxi | 0.2261 | Chongqing | 0.4667 | Ningxia | 0.1429 |

| Jilin | 0.3419 | Shandong | 0.6046 | Sichuan | 0.2558 | Xinjiang | 0.1391 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.2463 | Henan | 0.3925 | Guizhou | 0.0348 | China | 0.4371 |

Table 4 The population dynamics and urbanization investment in China and its provinces for 2015-2030 |

| Provincial regions | The total popula- tion in 2030 (million) | Urban population in 2030 (million) | Urban reproduction population by itself (million) | Rural to urban population (million) | Population of urban growth (ten thousand) | New-type urbanization construction funds needed in yuan (trillion) | The proportion of funds accounted (%) | GDP in yuan (trillion) | Urbaniza- tion funds as a percentage of GDP (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 2992.12 | 2975.96 | 198.1 | 923.25 | 1121.35 | 3.07 | 2.91 | 53.6 | 5.73 |

| Tianjin | 1604.24 | 1582.42 | 105.34 | 446.25 | 551.59 | 1.51 | 1.43 | 31.5 | 4.79 |

| Hebei | 7500.32 | 4838.46 | 322.09 | 1477.44 | 1799.53 | 4.92 | 4.67 | 74.87 | 6.57 |

| Shanxi | 4729.47 | 3276.1 | 218.1 | 1049.87 | 1267.97 | 3.46 | 3.28 | 35.46 | 9.76 |

| Inner Mongolia | 2524.87 | 1896.43 | 126.25 | 489.21 | 615.46 | 1.69 | 1.6 | 48.65 | 3.47 |

| Liaoning | 4388.53 | 3337.04 | 222.15 | 710.59 | 932.74 | 2.56 | 2.43 | 72.24 | 3.54 |

| Jilin | 2800.62 | 1736.94 | 115.63 | 328.77 | 444.4 | 1.22 | 1.16 | 34.8 | 3.51 |

| Heilongjiang | 3760.28 | 2359.2 | 157.05 | 382.82 | 539.87 | 1.49 | 1.41 | 38.59 | 3.86 |

| Shanghai | 3011.63 | 3008.32 | 200.26 | 937.24 | 1137.5 | 3.1 | 2.94 | 63.49 | 4.88 |

| Jiangsu | 8170.34 | 7363.93 | 490.22 | 2209.68 | 2699.9 | 7.37 | 6.99 | 157.33 | 4.68 |

| Zhejiang | 5946.81 | 5692.88 | 378.98 | 2089.71 | 2468.69 | 6.73 | 6.39 | 98.13 | 6.86 |

| Anhui | 6059.4 | 3993.14 | 265.83 | 1112.78 | 1378.61 | 3.77 | 3.58 | 50.14 | 7.52 |

| Fujian | 4068.7 | 3637.01 | 242.11 | 1205.9 | 1448.01 | 3.95 | 3.75 | 56.57 | 6.98 |

| Jiangxi | 4680.76 | 3015.81 | 200.76 | 888.5 | 1089.26 | 2.98 | 2.83 | 38.1 | 7.82 |

| Shandong | 9799.01 | 7315.94 | 487.03 | 2079.85 | 2566.88 | 7.01 | 6.65 | 141.5 | 4.95 |

| Henan | 9494.06 | 5635.67 | 375.16 | 1584.68 | 1959.84 | 5.36 | 5.09 | 83.78 | 6.4 |

| Hubei | 5563.67 | 3781.07 | 251.72 | 909.88 | 1161.6 | 3.18 | 3.02 | 65.31 | 4.87 |

| Hunan | 6415.51 | 4321.49 | 287.69 | 1206.37 | 1494.06 | 4.09 | 3.88 | 66.13 | 6.18 |

| Guangdong | 14470.67 | 13901.97 | 925.45 | 5381.01 | 6306.46 | 17.17 | 16.29 | 164.42 | 10.44 |

| Guangxi | 4853.91 | 3053.11 | 203.24 | 865.63 | 1068.87 | 2.92 | 2.77 | 38.92 | 7.5 |

| Hainan | 1066.6 | 766.46 | 51.03 | 255.15 | 306.18 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 10.39 | 7.99 |

| Chongqing | 2690.93 | 2235.89 | 148.85 | 601.95 | 750.8 | 2.05 | 1.95 | 34.14 | 6 |

| Sichuan | 7785.76 | 4853.64 | 323.12 | 1289.88 | 1613 | 4.41 | 4.18 | 69.93 | 6.31 |

| Guizhou | 3701.6 | 1841.92 | 122.62 | 509.82 | 632.44 | 1.73 | 1.64 | 17.81 | 9.71 |

| Yunnan | 5194.26 | 2842.3 | 189.22 | 923.6 | 1112.82 | 3.03 | 2.88 | 29.69 | 10.21 |

| Tibet | 366.95 | 117.5 | 7.83 | 35.93 | 43.76 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 1.98 | 6.06 |

| Shaanxi | 3844.83 | 2569.5 | 171.06 | 737.61 | 908.67 | 2.48 | 2.35 | 42.88 | 5.78 |

| Gansu | 2709.57 | 1310.89 | 87.27 | 368.2 | 455.47 | 1.24 | 1.18 | 16.16 | 7.67 |

| Qinghai | 649.93 | 363.44 | 24.2 | 99.82 | 124.02 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 5.44 | 6.25 |

| Ningxia | 783.91 | 496.53 | 33.05 | 156.82 | 189.87 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 7.26 | 7.16 |

| Xinjiang | 2896.73 | 1275.14 | 84.88 | 309.75 | 394.63 | 1.08 | 1.02 | 21.44 | 5.04 |

| China | 144526 | 101341.63 | 7016.26 | 31567.96 | 38584.22 | 105.38 | 100 | 1649.21 | 6.39 |

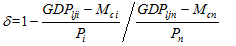

Table 5 The investment intensity index of China’s new-type urbanization construction for 2015-2030 |

| Provincial regions | δ | Region | δ | Provincial regions | δ | Region | δ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guizhou | 0.5933 | Anhui | 0.2836 | Heilongjiang | 0.0764 | Shandong | -0.2849 |

| Tibet | 0.5255 | Qinghai | 0.2654 | Guangdong | 0.0474 | Zhejiang | -0.4388 |

| Yunnan | 0.5195 | Henan | 0.2267 | Shaanxi | 0.0163 | Liaoning | -0.4864 |

| Gansu | 0.4845 | Sichuan | 0.2122 | Entire country | 0.0000 | Beijing | -0.5809 |

| Shanxi | 0.3666 | Ningxia | 0.1951 | Hubei | -0.0454 | Jiangsu | -0.7182 |

| Xinjiang | 0.3420 | Hainan | 0.1609 | Chongqing | -0.1164 | Inner Mongolia | -0.7412 |

| Guangxi | 0.3057 | Hebei | 0.1269 | Jilin | -0.1225 | Tianjin | -0.7501 |

| Jiangxi | 0.2976 | Hunan | 0.0947 | Fujian | -0.2107 | Shanghai | -0.8772 |

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

| 40 |

|

| 41 |

|

| 42 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 44 |

|

| 45 |

|

| 46 |

|

| 47 |

|

| 48 |

|

| 49 |

|

| 50 |

The EIU China Research Team, 2014. China urbanization in 2003. China Police Review, 19(7): 93-98. (in Chinese)

|

| 51 |

The Research Group of the State Council Development Research Center (RGSCDRC), 2011. Citizenizing the Rural Migrants. Beijing: China Development Press. (in Chinese)

|

| 52 |

|

| 53 |

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2013. China National Human Development Report 2013. Beijing: China Translation & Publishing Corporation.

|

| 54 |

|

| 55 |

|

| 56 |

|

| 57 |

|

| 58 |

|

| 59 |

|

| 60 |

|

| 61 |

|

| 62 |

|

| 63 |

|

| 64 |

|

| 65 |

|

| 66 |

|

| 67 |

|

| 68 |

|

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |